What Donovan experienced at KENFIG

Extract from Edward Donovan’s 1805 Excursion through South Wales

A narrow road turns off to the southward from Margam, that leads in a direct course to the verge of the sandy heath, on which we met with the village of Kenfig ; a cluster of mean cottages, grouped together with its church on a ridge of rising ground that overlooks the heath, and commands, on the other side, a boundless view of the channel.- — At the commencement of our walk from Margam in the way thither, we passed Eggwlys Nunne [sic], an extensive tract of land that belonged to the church before the dissolution, as the name implies. About three quarters of a mile upon this road, we also saw the small stone pillar which Camden describes as standing here in his days. This serves as a kind of land-mark, occupying a spot upon the bank on the left hand side of the road, in a direction due south from the village we were leaving. It is a quadrangular column, above four feet and more than one in breadth on each side. The two words Pumpeius Carantorius, cut in rude roman letters on one of the sides of this stone, may be still distinctly read. Antiquaries admit this to be the monument of a Roman. The Welsh are of a different opinion. Camden tells us, that by adding and altering, they read the inscription thus ; Pim bis an car antopius, qod. and explains it in the following manner. “ The five fingers of our friends, our neighbours slew us,” believing it to be the sepulchre of Morgan the prince, from whom the county took its name, and who they say was slain eight hundred years before Christ. — The lands, as we sauntered on, appeared to be in good condition, with many respectable farm houses sprinkled over it, till the road bends towards the sandy heath that separates these lands from Kenfig, and there at once every trace of culture and society appeared to have forsaken us. The distant tower of the church defined the spot which Kenfig occupies, and with the assistance of a friendly cart track, directed our footsteps with some little certainty the best way towards it.

But before we reached the place, we were overtaken by the honest fellow that had shewn us the church of Margam, who perceiving from our enquiries we were strangers, and apprehending we might encounter some difficulty in finding the old castle and pool of Kenfig, which he knew to be the object of our journey when we parted with him, had put up his lime truck, with which we left him at work for the day : and without waiting for saddle or bridle, save a lime sack and a halter, had mounted his pony, and set off at full gallop after us.

On the event of this meeting, we had reason to congratulate ourselves soon after; Kenfig to our astonishment as we perceived in the sequel of the day’s adventure, harbours a desperate banditti of lurking fellows, who obtain a very profitable livelihood by the illicit traffic carried on upon this coast in the smuggling line, the plunder of wrecks, and the like, and whose haunts of course it behoves the stranger to avoid, or visit with caution. We did not escape the threats of these brutal pilferers, for daring as they conceived to pry into their concerns, and if we had not been under the watchful eye of one who knew them, and would certainly have led to their detection, we have every reason to believe that consequences of a much more serious nature must have ensued.

A neat modern monument enclosed within a rail-work of iron, stands in the burying ground near the West end of the church, deserving of attention. On the south side we observed a large coffin-like stone, embellished with an elegant flowery cross. It is of the earliest Norman age, and very similar in appearance to that of Morice de Lundres in Ewenny priory. We were prevented from taking a drawing of this by the boisterous intrusion of a party of fellows, who after abusing us in the village, had followed us to the church. The sight of the pencil and memorandum book, furnished a sufficient pretext for their interruption. “ Yes, certainly they are spies,” exclaimed one of them, the rest rejoining that he must be right. Here our conductor, who had hitherto observed uncommon silence, with a mixture of surprize and resolution addressed himself to them in their native tongue, and finding his expostulations ineffectual, whispered softly in my ear, “be cautious,” — “ they are dangerous “ They are not so ignorant (continued this man very generously) as to suppose you are spies, because you are examining an old tomb-stone, but they are wicked enough for anything, and I must say, though they are my own country-folks, under the pretence of securing you for spies, they might first plunder you, and then perhaps murder you to prevent discovery. ’’—According to his advice, we left the place immediately ; a volley of menace accompanying us, as we crossed the sand banks, but these we disregarded, perceiving that none of the people were inclined to follow us, and taking a circuitous route across the sands, soon came in sight of the lake of Kenfig.

This pool of water being esteemed a singular geological curiosity, deserves particular mention. We were ourselves at the first glance surprised to find such a body of fresh water in this situation. The water is embosomed in a depression of an irregular form, in the midst of sands that have been apparently drifted upon this spot from the contiguous coast, and though lying within a very short distance of the sea at flood tide, invariably retains its freshness, pure and untainted by the muriatic properties of the former. The circumference of this pool is estimated at a mile and three quarters. The depth is in some places. Indeed it has the reputation of being in many parts unfathomable,- or in other words, after many trials the greater depths have not yet been ascertained.

The story of the country is, that in former times, beyond the reach of history, a town or city standing in this very spot, was swallowed up in the night time by an earthquake. In the morning, the people say the town had entirely disappeared, and nothing was to be seen in the place of it but this pool of water which, rushing from secret springs in the bowels of the earth, had completely filled the cavity the shock occasioned. — Similar stories are related of some other lakes and pools in Wales, with what degree of truth is here unnecessary to enquire. There is nothing absurd in admitting the possibility of the fact, so far as relates to this individual spot. But we are inclined to think the tale arose from another circumstance much more plausible, and better authenticated. The pen of history records the destruction of the old town of Kenfig, that was standing in the time of the Clares, soon after the conquest, by the dreadful ravages of the sands driven from the shore of the Severn sea. The town in a little time was completely overwhelmed, and the inhabitants being compelled to desert it, in order to preserve them-selves secure from a repetition of the same calamity, built another town upon the lofty ridge of land on which the village bearing that name remains at this day. Those circumstances tend to confirm the notion entertained by some, that the old town actually occupied a station near this pool, which being inundated with sands at the same time as the lands surrounding, its pent up waters would naturally be constrained to shift their position, and perchance, by overflowing its former boundaries, might eventually contribute to the dissolution of the town, and thus afford some colour of authority to the disastrous tale which tradition magnifies .

[in a note: ed.] We received the most positive assurance of some fishermen near this spot, who had been occasionally employed to take fish from the pool, that ruins of the buildings belonging to the old town are still To be seen in two or three places below the surface of the water - The value of this local trait of information we cannot possibly appreciate, as we had no means of satisfying our minds respecting it. [end of note]

The water of Kenfig pool is not merely fresh, but pure, crystalline, and of a pleasant flavour, as we found on tasting it. To determine only the freshness of the water, no such precaution was requisite, because a slight attention to its spontaneous products was sufficient to prove the fact. They are such as are peculiar to fresh waters only. — Those who possess an ordinary acquaintance with the science of nature, well know with what unerring precision the great Author of the Universe has defined the sphere in which every creature is destined to fulfil the purposes of that life bestowed upon it : the element most congenial with its habits; and the means best calculated to supply its wants. — The situation most convenient for the growth of the humblest vegetable; or the station suitable to every inanimate body. — And really I scarcely ever remember to have witnessed this distribution of Providence marked more definitively than within the compass of a mile or two about this spot. The pool, the heath, the beach embathed with the tribute of the advancing waves, and the intervening track of sands, producing each a distinct variety of living creatures, or vegetables peculiar to the various situations that occur here. — The shallows of the pool near the shore is overmantled with aquatic plants, among which the Nympha alba, displaying at this time a profusion of its lovely white blossoms, appeared most conspicuous . (We also gathered viola lutea in plenty on the adjacent Heath.)

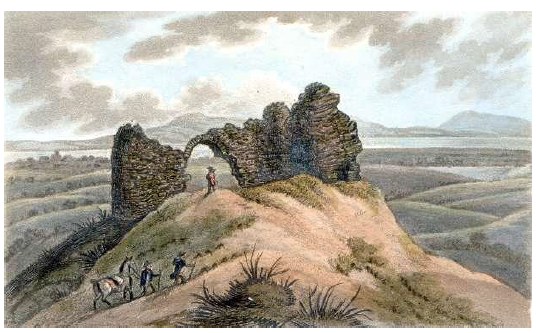

The ruin of Kenfig castle, from the obscurity of its situation, is rarely visited by strangers. It lies at a distance from this pool, upon a small eminence, surrounded by a cluster of sand hills, in the midst of a sandy plain that stretches along one side of the village.

Fancy is bewildered in contemplating the solitary remains of this ancient fortress. What has been its primitive form ? — What its original extent? These are questions which advert to mind, but remain unanswered. We perceive at once that it must have risen to a far greater height above the plain than it does at this period, because the foundations, and even the walls, lie buried under the ever shifting surface of the sands, or only just emerge above their level.

Those who imagine that it belonged in the first instance to the Stradlings of St. Donat’s; or to the lords of Ogmore, are alike misled ; and it is equally certain that the building served a more important purpose than that of an advanced post for making observations towards the bay of Swansea (vide Evans Tour). We are not disposed to reject traditionary information on trivial grounds. The people of the country are persuaded that it was the castellated residence of Fitzhamon for some years after he overcame Glamorganshire, during which time the castle of Cardiff was rebuilding, and this tradition I am inclined to admit. Can the rational mind distrust the truth of an assertion founded on the traditional belief of the country, when that belief is confirmed by the collateral testimony of authentic history ? We are expressly told by Caradoc, that the town and castle of Kenfig, the town of Cowbridge, or Pont Vaen, and the town and castle of Cardiff were retained by Fitzhamon as his share of the conquest. Further, it is stated by Sir Edward Stradling, Knt. the lineal descendant of the first lord of St. Donat’s (writing in 1575), several centuries after, that “ the castles of Cardiff, and Kenfig, with the three market towns of Cardiff, Kenfig, and Cowbridge, being the body of the lordship of Glamorgan, were reserved by the lord (Fitzhamon) for himself and his heirs.” The words of Leland would seem to confirm the idea that the castle of Kenfig, together with the town, remained in the possession of Fitzhamon’s descendants ages after. “Kenfig, ” observes the writer (Leland), “was in the Clares tyme a Borrow Town, &c.” and Fitzhamon was indisputably the great ancestor of this branch of the Clare family. The first possessor of that name was Sir Gilbert de Clare, who married Amicia, the second daughter of William earl of Gloucester. She was the fourth in descent from Fitzhamon; Her son, Sir Gilbert de Clare, so called after his father, succeeded. The Clare family retained the estate till the reign of Edward the Second, when Sir Gilbert de Clare, the ninth lord of Glamorgan, was slain by the Scots, and the estate devolved to his three sisters. The eldest, Eleanor, marrying the younger Hugh Spenser, the latter succeeded to the title (Caradoc. Vide Powel). Nothing is more plausible than the suggestion that Kenfig castle during all this time belonged to the lords of this estate, yet have the authority of a petition presented by this Spenser, or his son, to Edward the Second, to prove that it appertained to the lordship in after times. This petition complains, that among others the castle of Kenfig had been plundered and burnt by the earl of Hereford, Roger Mortimer, and his nephew, who were confederated against him. The castle must have been replaced in a respectable state of defence after that time, since in the reign of Henry the Fourth we find it capable of making resistance to the victorious arms of Owen Glyndwr, by whom it was taken, dismantled, and reduced to ruin.

The style of this building, so far as can be observed in the shattered remnant of a wall and a single arch-way, appears to be rather ancient. Perhaps, indeed, it may be referred with safety to the earliest era mentioned in this history. The form of the mount on which it stands, with the traces of the walls, prove this part to have been somewhat circular, and about seventy-five feet in diameter. The aspect of this ruin, its size, and situation, and every circumstance of its history, concur to persuade us that this is nothing more than the remains .of the keep and consequently only part of a much larger building, long since dilapidated, and buried in the sands. (Leland speaks of it in these terms about the year 1538. ” There is a litle village on the est side of Kenfik and a Castl boath in Ruin and almost shokid and devourid with the sands that the Severn castith up.” Vol. 4. 67. )

Extract from Edward Donovan’s 1805 Excursion through South Wales

A narrow road turns off to the southward from Margam, that leads in a direct course to the verge of the sandy heath, on which we met with the village of Kenfig ; a cluster of mean cottages, grouped together with its church on a ridge of rising ground that overlooks the heath, and commands, on the other side, a boundless view of the channel.- — At the commencement of our walk from Margam in the way thither, we passed Eggwlys Nunne [sic], an extensive tract of land that belonged to the church before the dissolution, as the name implies. About three quarters of a mile upon this road, we also saw the small stone pillar which Camden describes as standing here in his days. This serves as a kind of land-mark, occupying a spot upon the bank on the left hand side of the road, in a direction due south from the village we were leaving. It is a quadrangular column, above four feet and more than one in breadth on each side. The two words Pumpeius Carantorius, cut in rude roman letters on one of the sides of this stone, may be still distinctly read. Antiquaries admit this to be the monument of a Roman. The Welsh are of a different opinion. Camden tells us, that by adding and altering, they read the inscription thus ; Pim bis an car antopius, qod. and explains it in the following manner. “ The five fingers of our friends, our neighbours slew us,” believing it to be the sepulchre of Morgan the prince, from whom the county took its name, and who they say was slain eight hundred years before Christ. — The lands, as we sauntered on, appeared to be in good condition, with many respectable farm houses sprinkled over it, till the road bends towards the sandy heath that separates these lands from Kenfig, and there at once every trace of culture and society appeared to have forsaken us. The distant tower of the church defined the spot which Kenfig occupies, and with the assistance of a friendly cart track, directed our footsteps with some little certainty the best way towards it.

But before we reached the place, we were overtaken by the honest fellow that had shewn us the church of Margam, who perceiving from our enquiries we were strangers, and apprehending we might encounter some difficulty in finding the old castle and pool of Kenfig, which he knew to be the object of our journey when we parted with him, had put up his lime truck, with which we left him at work for the day : and without waiting for saddle or bridle, save a lime sack and a halter, had mounted his pony, and set off at full gallop after us.

On the event of this meeting, we had reason to congratulate ourselves soon after; Kenfig to our astonishment as we perceived in the sequel of the day’s adventure, harbours a desperate banditti of lurking fellows, who obtain a very profitable livelihood by the illicit traffic carried on upon this coast in the smuggling line, the plunder of wrecks, and the like, and whose haunts of course it behoves the stranger to avoid, or visit with caution. We did not escape the threats of these brutal pilferers, for daring as they conceived to pry into their concerns, and if we had not been under the watchful eye of one who knew them, and would certainly have led to their detection, we have every reason to believe that consequences of a much more serious nature must have ensued.

A neat modern monument enclosed within a rail-work of iron, stands in the burying ground near the West end of the church, deserving of attention. On the south side we observed a large coffin-like stone, embellished with an elegant flowery cross. It is of the earliest Norman age, and very similar in appearance to that of Morice de Lundres in Ewenny priory. We were prevented from taking a drawing of this by the boisterous intrusion of a party of fellows, who after abusing us in the village, had followed us to the church. The sight of the pencil and memorandum book, furnished a sufficient pretext for their interruption. “ Yes, certainly they are spies,” exclaimed one of them, the rest rejoining that he must be right. Here our conductor, who had hitherto observed uncommon silence, with a mixture of surprize and resolution addressed himself to them in their native tongue, and finding his expostulations ineffectual, whispered softly in my ear, “be cautious,” — “ they are dangerous “ They are not so ignorant (continued this man very generously) as to suppose you are spies, because you are examining an old tomb-stone, but they are wicked enough for anything, and I must say, though they are my own country-folks, under the pretence of securing you for spies, they might first plunder you, and then perhaps murder you to prevent discovery. ’’—According to his advice, we left the place immediately ; a volley of menace accompanying us, as we crossed the sand banks, but these we disregarded, perceiving that none of the people were inclined to follow us, and taking a circuitous route across the sands, soon came in sight of the lake of Kenfig.

This pool of water being esteemed a singular geological curiosity, deserves particular mention. We were ourselves at the first glance surprised to find such a body of fresh water in this situation. The water is embosomed in a depression of an irregular form, in the midst of sands that have been apparently drifted upon this spot from the contiguous coast, and though lying within a very short distance of the sea at flood tide, invariably retains its freshness, pure and untainted by the muriatic properties of the former. The circumference of this pool is estimated at a mile and three quarters. The depth is in some places. Indeed it has the reputation of being in many parts unfathomable,- or in other words, after many trials the greater depths have not yet been ascertained.

The story of the country is, that in former times, beyond the reach of history, a town or city standing in this very spot, was swallowed up in the night time by an earthquake. In the morning, the people say the town had entirely disappeared, and nothing was to be seen in the place of it but this pool of water which, rushing from secret springs in the bowels of the earth, had completely filled the cavity the shock occasioned. — Similar stories are related of some other lakes and pools in Wales, with what degree of truth is here unnecessary to enquire. There is nothing absurd in admitting the possibility of the fact, so far as relates to this individual spot. But we are inclined to think the tale arose from another circumstance much more plausible, and better authenticated. The pen of history records the destruction of the old town of Kenfig, that was standing in the time of the Clares, soon after the conquest, by the dreadful ravages of the sands driven from the shore of the Severn sea. The town in a little time was completely overwhelmed, and the inhabitants being compelled to desert it, in order to preserve them-selves secure from a repetition of the same calamity, built another town upon the lofty ridge of land on which the village bearing that name remains at this day. Those circumstances tend to confirm the notion entertained by some, that the old town actually occupied a station near this pool, which being inundated with sands at the same time as the lands surrounding, its pent up waters would naturally be constrained to shift their position, and perchance, by overflowing its former boundaries, might eventually contribute to the dissolution of the town, and thus afford some colour of authority to the disastrous tale which tradition magnifies .

[in a note: ed.] We received the most positive assurance of some fishermen near this spot, who had been occasionally employed to take fish from the pool, that ruins of the buildings belonging to the old town are still To be seen in two or three places below the surface of the water - The value of this local trait of information we cannot possibly appreciate, as we had no means of satisfying our minds respecting it. [end of note]

The water of Kenfig pool is not merely fresh, but pure, crystalline, and of a pleasant flavour, as we found on tasting it. To determine only the freshness of the water, no such precaution was requisite, because a slight attention to its spontaneous products was sufficient to prove the fact. They are such as are peculiar to fresh waters only. — Those who possess an ordinary acquaintance with the science of nature, well know with what unerring precision the great Author of the Universe has defined the sphere in which every creature is destined to fulfil the purposes of that life bestowed upon it : the element most congenial with its habits; and the means best calculated to supply its wants. — The situation most convenient for the growth of the humblest vegetable; or the station suitable to every inanimate body. — And really I scarcely ever remember to have witnessed this distribution of Providence marked more definitively than within the compass of a mile or two about this spot. The pool, the heath, the beach embathed with the tribute of the advancing waves, and the intervening track of sands, producing each a distinct variety of living creatures, or vegetables peculiar to the various situations that occur here. — The shallows of the pool near the shore is overmantled with aquatic plants, among which the Nympha alba, displaying at this time a profusion of its lovely white blossoms, appeared most conspicuous . (We also gathered viola lutea in plenty on the adjacent Heath.)

The ruin of Kenfig castle, from the obscurity of its situation, is rarely visited by strangers. It lies at a distance from this pool, upon a small eminence, surrounded by a cluster of sand hills, in the midst of a sandy plain that stretches along one side of the village.

Fancy is bewildered in contemplating the solitary remains of this ancient fortress. What has been its primitive form ? — What its original extent? These are questions which advert to mind, but remain unanswered. We perceive at once that it must have risen to a far greater height above the plain than it does at this period, because the foundations, and even the walls, lie buried under the ever shifting surface of the sands, or only just emerge above their level.

Those who imagine that it belonged in the first instance to the Stradlings of St. Donat’s; or to the lords of Ogmore, are alike misled ; and it is equally certain that the building served a more important purpose than that of an advanced post for making observations towards the bay of Swansea (vide Evans Tour). We are not disposed to reject traditionary information on trivial grounds. The people of the country are persuaded that it was the castellated residence of Fitzhamon for some years after he overcame Glamorganshire, during which time the castle of Cardiff was rebuilding, and this tradition I am inclined to admit. Can the rational mind distrust the truth of an assertion founded on the traditional belief of the country, when that belief is confirmed by the collateral testimony of authentic history ? We are expressly told by Caradoc, that the town and castle of Kenfig, the town of Cowbridge, or Pont Vaen, and the town and castle of Cardiff were retained by Fitzhamon as his share of the conquest. Further, it is stated by Sir Edward Stradling, Knt. the lineal descendant of the first lord of St. Donat’s (writing in 1575), several centuries after, that “ the castles of Cardiff, and Kenfig, with the three market towns of Cardiff, Kenfig, and Cowbridge, being the body of the lordship of Glamorgan, were reserved by the lord (Fitzhamon) for himself and his heirs.” The words of Leland would seem to confirm the idea that the castle of Kenfig, together with the town, remained in the possession of Fitzhamon’s descendants ages after. “Kenfig, ” observes the writer (Leland), “was in the Clares tyme a Borrow Town, &c.” and Fitzhamon was indisputably the great ancestor of this branch of the Clare family. The first possessor of that name was Sir Gilbert de Clare, who married Amicia, the second daughter of William earl of Gloucester. She was the fourth in descent from Fitzhamon; Her son, Sir Gilbert de Clare, so called after his father, succeeded. The Clare family retained the estate till the reign of Edward the Second, when Sir Gilbert de Clare, the ninth lord of Glamorgan, was slain by the Scots, and the estate devolved to his three sisters. The eldest, Eleanor, marrying the younger Hugh Spenser, the latter succeeded to the title (Caradoc. Vide Powel). Nothing is more plausible than the suggestion that Kenfig castle during all this time belonged to the lords of this estate, yet have the authority of a petition presented by this Spenser, or his son, to Edward the Second, to prove that it appertained to the lordship in after times. This petition complains, that among others the castle of Kenfig had been plundered and burnt by the earl of Hereford, Roger Mortimer, and his nephew, who were confederated against him. The castle must have been replaced in a respectable state of defence after that time, since in the reign of Henry the Fourth we find it capable of making resistance to the victorious arms of Owen Glyndwr, by whom it was taken, dismantled, and reduced to ruin.

The style of this building, so far as can be observed in the shattered remnant of a wall and a single arch-way, appears to be rather ancient. Perhaps, indeed, it may be referred with safety to the earliest era mentioned in this history. The form of the mount on which it stands, with the traces of the walls, prove this part to have been somewhat circular, and about seventy-five feet in diameter. The aspect of this ruin, its size, and situation, and every circumstance of its history, concur to persuade us that this is nothing more than the remains .of the keep and consequently only part of a much larger building, long since dilapidated, and buried in the sands. (Leland speaks of it in these terms about the year 1538. ” There is a litle village on the est side of Kenfik and a Castl boath in Ruin and almost shokid and devourid with the sands that the Severn castith up.” Vol. 4. 67. )